Apache Spark Shared Variables - Broadcast Variables and Accumulators Explained

In a distributed system like Apache Spark, your code doesn’t run on a single machine — it runs in parallel across multiple executors. Normally, each executor works with its own copy of data and cannot directly modify or share it with others. But what if you want to share read-only data efficiently across nodes? Or aggregate values from multiple tasks back to the driver?

That’s where Shared Variables come in.

Shared variables allow Spark programs to efficiently share data and state across distributed tasks without relying on expensive data transfer or external storage. Spark provides two important types of shared variables:

Broadcast Variables – share read-only data efficiently with all executors

Accumulators – aggregate values from executors and send results back to the driver

These play a key role in performance optimization, logging, debugging workflows, and advanced analytics.

Why Shared Variables are needed?

Apache Spark runs code in a distributed environment, which means your program isn’t executed on a single machine. Instead, it is split into multiple tasks that run independently across different executors. While this parallelism enables high-speed processing, it also introduces a challenge:

Each executor operates with its own copy of the variables and cannot see or modify variables that exist on the driver or on another executor.

Let’s say you declare a simple Python list or a counter variable in your Spark code. When Spark sends your functions to the cluster:

The variable is serialized and shipped with each task

Each executor receives its own separate copy

Changes made inside executors do not propagate back to the driver

Repeated copying of the same variable causes network overhead and slows down the job

This behavior is intentional — distributed systems avoid shared mutable state to prevent conflicts and race conditions.

But it becomes inefficient or even impossible in some real-world use cases, like:

Referencing the same lookup table in millions of tasks

Without sharing: It would be sent again with every task

Counting invalid records during ETL

Without accumulation: No centralized place to track updated counts

In short:

Spark’s default design isolates tasks for scalability and safety, but sometimes we need controlled, efficient communication or state-sharing across nodes.

Shared variables solve this exact problem by providing:

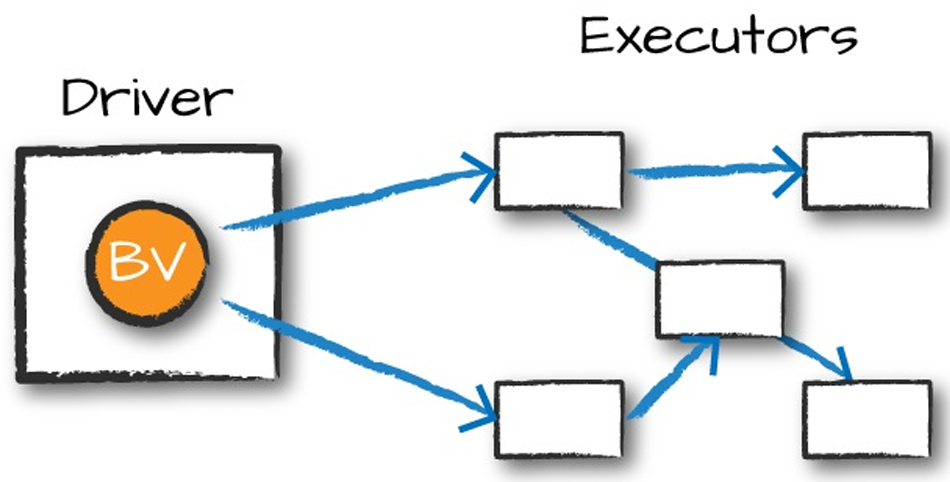

One-way read-sharing (Broadcast Variables) → Driver → Executors

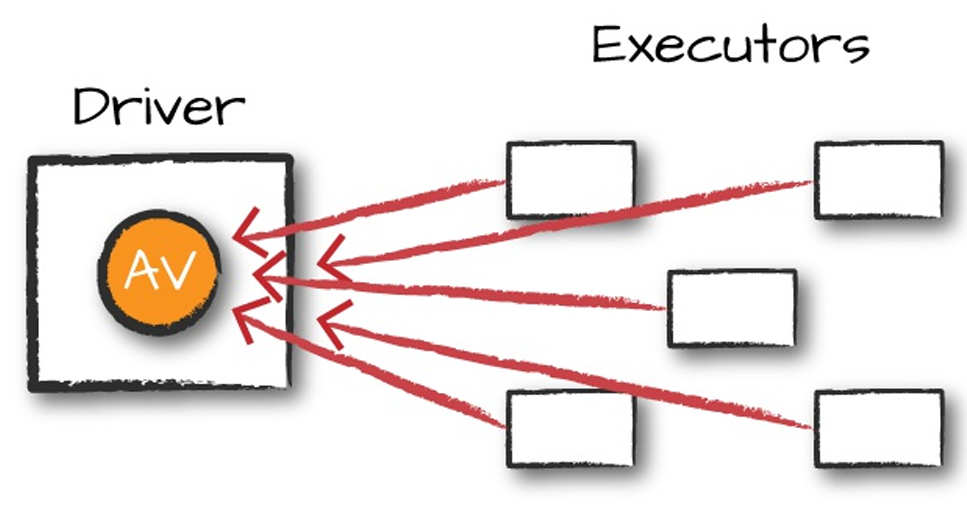

One-way aggregation (Accumulators) → Executors → Driver

They preserve Spark’s distributed model while enabling coordinated access to certain values, improving both performance and analytics visibility.

Broadcast Variables – The One-Copy-Per-Node Superpower

Imagine you have a 250 MB country-to-currency lookup table, or a 1.8 GB ML embedding matrix, or a 400 MB list of blocked IP ranges. Every single task on every executor needs it — right now.

If you just drop that object into a regular closure (a normal Scala/Python function), Spark will cheerfully serialize and ship those hundreds of megabytes once per task. On a 500-node cluster with 4 cores each, that’s 2 000 copies flying across the network, every single time you run an action. You just turned a 10-minute job into a 3-hour network bloodbath.

Broadcast variables fix this with one simple rule: send it once per executor, cache it in memory, and reuse forever.

Spark uses an efficient BitTorrent-style protocol behind the scenes: the driver sends the data to a few executors, those executors gossip it to others, and within seconds every node has its own local copy. After that, every task just grabs the local version — zero extra serialization, zero extra network.

When Spark executes transformation using map() or reduce() operations, it executes the transformations on a remote node by using the variables that are shipped with the tasks and these variables are not sent back to PySpark Driver hence there is no capability to reuse and sharing the variables across tasks.

Broadcast read-only Variables - Broadcast variables are read-only shared variables that are cached and available on all nodes in a cluster in-order to access or use by the tasks. Instead of sending this data along with every task, PySpark distributes broadcast variables to the machine using efficient broadcast algorithms to reduce communication costs. Note that broadcast variables are not sent to executors with sc.broadcast(variable) call instead, they will be sent to executors when they are first used.

When you run a PySpark RDD job that has the Broadcast variables defined and used, PySpark does the following.

· PySpark breaks the job into stages that have distributed shuffling and actions are executed with in the stage.

· Later Stages are also broken into tasks.

· PySpark broadcasts the common data (reusable) needed by tasks within each stage.

· The broadcasted data is cache in serialized format and deserialized before executing each task.

· The PySpark Broadcast is created using the broadcast(v) method of the SparkContext class. This method takes the argument v that you want to broadcast.

Real-World Example That Actually Matters

Let’s say you run a global e-commerce platform and you need to convert every transaction to USD in real time using today’s exchange rates.

# Driver node – runs once at job startup

exchange_rates = {

"USD": 1.0,

"EUR": 0.937,

"GBP": 0.789,

"JPY": 149.32,

"INR": 83.91,

# ... 180 more currencies – total ~300 KB (or 300 MB if you include historical rates)

}

# This is the magic line – happens once, costs almost nothing

rates_broadcast = spark.sparkContext.broadcast(exchange_rates)

# Now inside any transformation (RDD, DataFrame, Dataset, UDF – doesn't matter)

def convert_to_usd(amount: float, currency: str) -> float:

rate = rates_broadcast.value.get(currency, 1.0) # zero network cost!

return round(amount * rate, 2)

# Use it anywhere – here with DataFrame API

from pyspark.sql.functions import udf

from pyspark.sql.types import DoubleType

convert_udf = udf(convert_to_usd, DoubleType())

enriched = transactions_df.withColumn(

"amount_usd",

convert_udf(col("amount"), col("currency"))

)That rates_broadcast.value call is completely free — no serialization, no network shuffle, even if you have 10 000 tasks.

Another classic example of this:

# Old-school RDD version (still works perfectly in 2025)

sentence = "Spark The Definitive Guide : Big Data Processing Made Simple"

words = spark.sparkContext.parallelize(sentence.split(), 8)

# Imagine this dictionary is actually 800 MB of product metadata

word_values = {"Spark": 5000, "Definitive": 2500, "Big": -500, "Simple": 100}

values_bc = spark.sparkContext.broadcast(word_values)

enriched_rdd = (words

.map(lambda word: (word, values_bc.value.get(word, 0)))

.sortBy(lambda pair: pair[1], ascending=False))

enriched_rdd.collect()

# [('Spark', 5000), ('Definitive', 2500), ('Simple', 100), ('Big', -500), ...]When You Should (and Shouldn’t) Broadcast

| Do broadcast | Don’t broadcast |

|---|---|

| < 2 GB (fits comfortably in executor RAM) | > 10 GB (risk OOM on executors) |

| Read-only for the lifetime of the job | Data that changes every few minutes |

| Used in many tasks / multiple stages | Tiny lookup used only once |

| ML model weights, config maps, tax tables, stop-word lists, geo data, etc. | Frequently updated counters or metrics |

Modern Spark 3.5+ Alternatives (You Still Need Broadcast Sometimes)

spark.sql.execution.arrow.pyspark.enabled + Pandas UDFs → great for vectorised lookups

Delta Lake cache + broadcast hint → JOIN with /*+ BROADCAST */

Spark’s built-in broadcast join (automatic when table < spark.sql.autoBroadcastJoinThreshold)

But when you need explicit control, or the data isn’t a DataFrame (e.g., inside complex UDF logic), the classic spark.sparkContext.broadcast() is still the gold standard in 2025.

Bottom line: if you ever find yourself putting a big dictionary or model inside a lambda/closure and wondering why your job is slow and network-bound — you’ve just discovered the perfect use case for a broadcast variable. One line of code, massive real-world impact.

Accumulators – The Indestructible Counters That Survive Crashes, Retries, and Chaos

Picture this: it’s 2026, your 800-node Spark cluster just lost 47 executors during a Black Friday surge, half your tasks got retried, and yet — when the dust settles — the single number suspicious_transactions_detected.value is still exactly correct. No off-by-one, no race condition, no “we lost count during the failover” ticket.

That’s the quiet superpower of accumulators: distributed, fault-tolerant, add-only variables that only move in one direction (up) and only using associative/commutative operations. Spark guarantees that even if a task dies and restarts three times, its contribution is applied exactly once in actions — and at worst twice in transformations (which is usually fine for counters).

They’re the reason every production job still has at least one accumulator named “bad_records”, “poison_messages”, or “fraud_score_above_95”.

An Example to Consider

from pyspark import AccumulatorParam

# Classic Long accumulator (built-in)

bad_records = spark.sparkContext.accumulator(0)

# Named version – appears beautifully in Spark UI

china_flights = spark.sparkContext.longAccumulator("Flights_To_Or_From_China")

# Custom accumulator for sets (e.g., track unique corrupt keys)

class SetAccumulator(AccumulatorParam):

def zero(self, init): return set()

def addInPlace(self, s1, s2): return s1 | s2

corrupt_keys = spark.sparkContext.accumulator(set(), SetAccumulator())

spark.sparkContext.register(corrupt_keys, "Unique_Corrupt_Keys")Now use them inside any transformation or action:

def process_row(row):

try:

# your complex parsing / ML inference / enrichment logic

cleaned = complex_pipeline(row)

if cleaned.destination == "China" or cleaned.origin == "China":

china_flights.add(cleaned.passenger_count)

return cleaned

except Exception as e:

bad_records.add(1) # survives task retries!

corrupt_keys.add(row.message_id) # unique bad keys, no duplicates

return None

# Works on DataFrames too!

(cleaned_df

.foreach(process_row) # action → exactly-once guarantees

.write.parquet("s3://clean/..."))After the job finishes (or even while it’s running), just read the truth:

print(f"Bad records: {bad_records.value}") # → 12 437

print(f"China passengers: {china_flights.value}") # → 1 847 292

print(f"Unique corrupt IDs: {len(corrupt_keys.value)}") # → 2 104

And yes — these numbers appear live in the Spark UI under the “Accumulators” tab the moment the first task reports them.

When to Reach for Accumulators (2025 Edition)

| Perfect for | Avoid for |

|---|---|

| Error / poison message counters | Business logic that affects output rows |

| Unique sets of bad keys / fraud IDs | Anything that needs subtract/divide |

| Custom metrics (latency buckets, feature stats) | High-cardinality aggregations (use groupBy instead) |

| Debugging “why is this job slow?” | Returning values to influence control flow |

Key Rules You Will Thank Yourself For Following

Use named accumulators in production → instant visibility in Spark UI

Only update inside actions (foreach, foreachPartition) if you need exactly-once

Transformations (map, filter) can update twice on retry → fine for counters, bad for money

Never read .value inside executors — only on driver after an action

Custom AccumulatorParam is still the easiest way to collect sets, lists, or histograms

Accumulators are boring, old, and absolutely indispensable. Every single production job that has ever survived a major incident owes part of its observability story to a handful of well-named accumulators.

Custom Accumulators – When Long Isn’t Enough

Sometimes you don’t just want a number — you want a set of bad keys, a histogram, or a list of the top 10 fraud patterns. That’s where custom accumulators shine.

Here’s the canonical 2025 example that appears in literally every serious Spark codebase:

from pyspark.accumulators import AccumulatorParam

class SetAccumulator(AccumulatorParam):

def zero(self, initial_value):

return set(initial_value)

def addInPlace(self, acc1, acc2):

if isinstance(acc2, set):

return acc1 | acc2

else:

acc1.add(acc2)

return acc1

# Production usage

suspicious_users = spark.sparkContext.accumulator(set(), SetAccumulator())

spark.sparkContext.register(suspicious_users, "Suspicious_User_IDs")

def detect_fraud(row):

if row.score > 0.98 and row.amount > 50000:

suspicious_users.add(row.user_id) # thread-safe, deduped, survives retries

return row

(enriched_df

.foreach(detect_fraud) # or inside mapPartitions, UDF, etc.

.write.parquet("s3://..."))After the job, one line on the driver gives you the truth:

print(f"High-risk users today: {len(suspicious_users.value)}")

# → High-risk users today: 184Other popular custom accumulators in the wild (2025):

VectorAccumulatorParam for histograms

TopNAccumulator for “top 10 worst merchants”

LatencyBucketAccumulator for p50/p95/p99 tracking

They cost almost nothing and turn opaque failures into instantly actionable insights.

Conclusion – The Two Shared Variables You’ll Never Outgrow

Broadcast variables and accumulators are over a decade old, yet in 2025 they remain irreplaceable:

Broadcast → the cheapest, most reliable way to push big read-only data to every executor.

Accumulators → the only safe, fault-tolerant way to count, collect, and debug across a planet-scale cluster.

DataFrames stole the spotlight, Spark 4.0 brought a thousand new features, but these two primitives quietly keep the world’s most critical jobs fast, observable, and correct.

Master them once, and you’ll never again watch a job mysteriously slow down because of a 300 MB lookup table being serialized 50 000 times… or wonder why your “error count” reset to zero after a task retry.