Spark Performance Tuning: The Direct Levers That Cut Hours From Your Spark Jobs

Last time we looked at the indirect factors – the architectural choices that quietly 10× your jobs before they even start. Now it’s time for the direct levers: the knobs you can twist in five minutes that instantly shave 30–90 % off runtimes on clusters you’re already paying for. These are the “low-hanging fruit” for a reason – they’re boring, mechanical, and stupidly effective. Whether it’s executor size vs count, shuffle partitions, join strategies, caching strategy, or AQE settings, one or two config changes (or a single repartition()) can turn a 4-hour nightmare into a 20-minute breeze. In this article we’re walking through every direct tuning lever, complete with real rules of thumb and the exact commands. No theory, no guessing – just the tweaks that work.

Parallelism

If a stage is taking forever, the very first fix is almost always “are we using all the cores we paid for?” A simple rule of thumb is brutal and timeless: aim for 2–4 tasks per CPU core on any stage that moves real data. Set the baseline once and forget it:

spark.sql.shuffle.partitions 2 × total_cores # e.g. 4000 for a 2000-core cluster

spark.default.parallelism 2 × total_cores # for RDDs & groupWith opsToo low → half your cluster sits idle. Too high → task overhead eats you alive. Check the Stages tab: if any stage has fewer tasks than 1.5 × cores, raise the number immediately.

Filter Early, Filter Aggressively

Pushing filters as far upstream as possible is free money. A .filter() or .where() before a join, aggregation, or even the first read can cut data volume (and therefore shuffle, memory, and CPU) by 90 %+. When the source supports predicate pushdown (Parquet, Delta, Iceberg, JDBC, etc.), Spark automatically skips entire files or blocks. Combine that with proper partitioning/bucketing and you often go from scanning terabytes to scanning gigabytes with zero code changes.

Repartition vs Coalesce – Know When to Pay for a Shuffle

After a big filter or when you’re about to cache or join, unbalanced partitions murder performance.

Want fewer partitions after a filter? Use coalesce() → no shuffle, just merges on the same executor.

Need perfectly even partitions or more of them? Bite the bullet and repartition() → expensive shuffle, but worth it before a heavy join or cache().

Example pattern that saves lives daily:

df.filter("year >= 2024")

.coalesce(400) // shrink cheaply after filter

.repartition($"user_id") // perfect balance before join or cache

.cache()Custom Partitioning (RDDs) – The Nuclear Option

99.9 % of jobs never need this in 2025. But if you’re stuck on RDDs and suffering horrific skew on a specific key, writing your own Partitioner subclass lets you control exactly where each key lands. It’s low-level, verbose, and fragile – treat it as a last resort after every Structured API trick has failed.

Kill Your UDFs (or at Least Starve Them)

Every Python or Scala UDF forces row-by-row serialization into JVM objects – the fastest way to make a 5-minute query take 50 minutes. The Structured API has a built-in function for almost everything now (including hyperbolic trig functions and IPv6 parsing). If you absolutely must keep a UDF, at minimum upgrade to vectorized/Pandas UDFs (Arrow-based) – they pass entire batches instead of one row at a time and routinely run 10–100× faster. Better yet: rewrite it in pure Spark SQL and watch it disappear from the slow part of the plan.

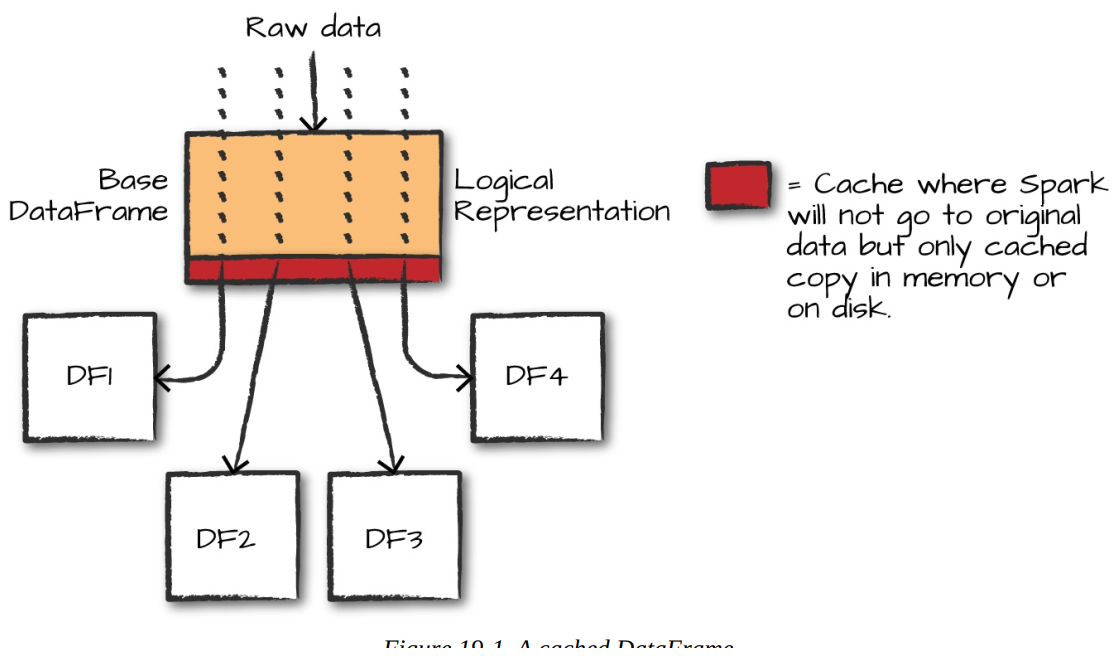

Temporary Data Storage (Caching) – The Double-Edged Sword That Can 10× or Tank Your Job

Caching is the single most powerful direct optimization in Spark when you truly reuse data multiple times – think iterative ML algorithms, interactive notebooks, or dashboard queries that hit the same cleaned table over and over. One .cache() call can turn a 30-minute job into 30 seconds because Spark keeps the DataFrame/RDD in memory (or disk) across the cluster and skips recomputing everything upstream.

But caching is also the fastest way to shoot yourself in the foot. Every cache() forces serialization, deserialization, and storage overhead – if you only touch the data once (or twice), you just made everything slower and wasted precious executor memory. The book is crystal clear: cache only when you will reuse the dataset at least 3–5 times in the same application. Otherwise you’re paying a heavy tax for zero benefit.

Use it like this:

val cleaned = df.filter(...).select(...).cache() // materialises on first action

cleaned.count() // forces caching now

// now reuse cleaned 10 more times → lightning fastKey gotchas to take home:

RDD caching stores the actual raw bytes.

DataFrame/SQL caching is plan-based – Spark caches the result of the current physical plan under the hood. This means two different DataFrames that happen to resolve to the same plan might silently share the same cached data. In a multi-user notebook environment this can be confusing (or dangerous) when one user’s cache suddenly affects another user’s query.

An example code to understand cache scenarios better:

# in Python

# Original loading code that does *not* cache DataFrame

DF1 = spark.read.format("csv")\

.option("inferSchema", "true")\

.option("header", "true")\

.load("/data/flight-data/csv/2015-summary.csv")

DF2 = DF1.groupBy("DEST_COUNTRY_NAME").count().collect()

DF3 = DF1.groupBy("ORIGIN_COUNTRY_NAME").count().collect()

DF4 = DF1.groupBy("count").count().collect()val lookup = spark.sparkContext.broadcast(loadLookupTable())

// inside map/foreach/UDF

val localCopy = lookup.valueHere’s what actually happens when you don’t cache: imagine one base DataFrame (let’s call it DF1) that reads and parses a big CSV (or worse – does expensive joins and window functions). Then you create DF2, DF3, and DF4, all branching off DF1. Without caching, every single collect() or count() you run forces Spark to start from scratch – re-reading the raw files, re-parsing every row, re-doing the same filters – three separate times. On small data this “only” costs a second or two per action, but on real production datasets it can waste hours.

Enter caching – the simplest way on earth to get 5-50× speedups. Just add two lines:

DF1.cache() # mark it for caching (still lazy)

DF1.count() # force the materialization right now

The first action (count()) triggers the full computation once and stores the resulting partitions in executor memory (or spills to disk if memory is tight). From that moment forward, DF2, DF3, DF4 – or any other operation – skip the entire upstream lineage and read straight from the cached version. In my own tests with the exact same code, runtime dropped from ~6 seconds to ~2 seconds instantly – more than 70 % faster with zero logic changes. Scale that to terabyte tables or heavy transformations and the savings become ridiculous.

By default .cache() is the same as .persist(StorageLevel.MEMORY_AND_DISK), meaning Spark keeps as much as possible in RAM and quietly writes the rest to local disk. If you want finer control (memory-only, disk-only, serialized, replicated, off-heap, etc.) just swap to .persist() with the exact StorageLevel you need. But for 95 % of real workloads, plain old DF.cache() plus one cheap action to materialize it is all the magic you’ll ever require. Do it once, reuse the data a dozen times, and watch your notebooks and batch jobs fly.

Joins – The Place Where Most Jobs Die (or Fly)

Nothing explodes runtime and memory usage faster than a badly planned join. Chapter 19’s battle-tested advice is still gospel:

Stick to equi-joins (==) whenever humanly possible – they’re the only ones Spark can truly optimize to perfection.

Filter first, join later – an inner join automatically drops rows that would never match, so put the more selective table on the left and let the optimizer kill billions of rows early.

Broadcast the small table (or add a /*+ BROADCAST */ hint) the moment one side fits in memory (default threshold is 10 MB, but bump it with spark.sql.autoBroadcastJoinThreshold). A broadcast join turns a shuffle-join bloodbath into a map-side operation – often 10–100× faster.

Never allow Cartesian joins to survive code review – they’re exponential death. Full outer joins are almost as bad; rewrite them as two filtered inner joins + union if you can.

Collect table/column statistics and bucket both sides on the join key → Spark can skip shuffles entirely and do map-side joins even on huge tables.

Do these five things and 90 % of your “join taking 8 hours” tickets disappear overnight.

Aggregations – Simple Rules, Massive Impact

There’s no magic aggregator wizard, but two habits separate slow jobs from fast ones:

Filter aggressively before the groupBy – every row you remove is one less row in the shuffle.

Keep shuffle partitions high enough (same 2–4× core count rule).

If you’re still on RDDs: never use groupByKey – it pulls all values for a key into a single list and OOMs instantly. Use reduceByKey, aggregateByKey, or combineByKey instead – they do partial pre-aggregation on the mapper side and shrink shuffle volume by orders of magnitude.

In 2025 the Structured API already does the right thing automatically, so just stay out of the RDD layer and you’re golden.

Broadcast Variables – Free Speed for Lookup Tables & Models

When the same reference data (country lookup, feature dictionary, trained ML model, etc.) is needed on every executor, don’t ship it with every task – that’s hundreds of gigabytes of waste. Broadcast it once:

Spark sends one read-only copy per node and reuses it forever. The savings are ridiculous: a 500 MB model that used to be serialized 10,000 times per stage now costs almost nothing. Use it for anything under a few gigabytes that doesn’t change during the job.

Wrap-up of Direct Levers

Parallelism, early filtering, smart repartition/coalesce, broadcast hints, proper caching, bucketed joins, and the occasional broadcast variable or reduceByKey – these are the boring, mechanical tweaks that turn 6-hour jobs into 6-minute jobs without spending an extra penny on hardware. Master them, apply them systematically, and you’ll spend way less time tuning and way more time shipping actual features.